The two factors that will lead to the financial downturn in 2019-2020

There are 2 streams of headwind facing most developed economies, which are threatening the growth that we’ve enjoyed in the past decade:

a) End of QE and rising interest rates

b) Inequality and the rise of social-political instability

Let’s explore these two points in-depth.

a) Rising interest rates and the eventual reversion to the mean in asset prices

At a simplistic level, when the debt/GDP ratio exceeds a certain point (between 100-200% depending on the country, the governor of the central bank and the macroeconomic climate), central banks tend to start tightening monetary policies in the form of raising the base interest rate. They will also start to impose stricter criteria on bank lending (e.g. which sector, what LTV ratio, etc), usually in the form of more stringent stress tests.

There are 4 key rationales behind tightening monetary policies:

- Central banks aim to keep inflation low: when economic growth gathers momentum, price level tends to increase, which leads to inflation. The base interest rate becomes the primary regulator as it cools down economic growth and central banks will have to bring it up in order to manage inflation.

- Controlled deleveraging: when the total debt within an economy exceeds a certain threshold, a large amount of the GDP will go towards interest payment, which is not the most productive use of capital. When companies pay an increasingly large amount of their profit to debt interests, it means lost investment in their employees (through training or better remuneration, which can be ultimately consumed to enhance growth) and lower tax revenue. Both are bad for economic growth.

- Central banks want to create an environment for greater capital allocation efficiency: linked to #2, a blanket low rate across all borrowing may not be channeling capital into the most productive sector, therefore by imposing more stringent/selective lending criteria, central banks can attempt to direct capital into the desired sectors.

- Central banks want to decelerate growth to prevent huge overheating, what will lead to even worse crises: investors believe that markets get nervous when the debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds a certain threshold and will automatically push up the cost of borrowing for governments, therefore central bankers would like to proactively decelerate growth to prevent overheating and enhance confidence.

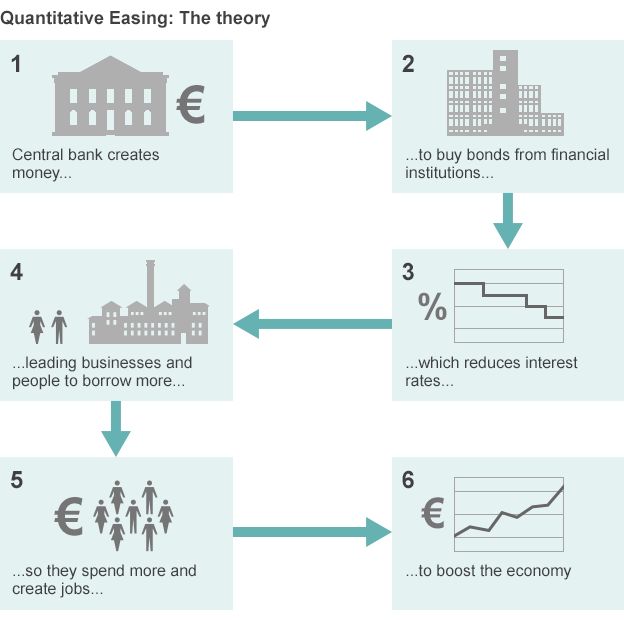

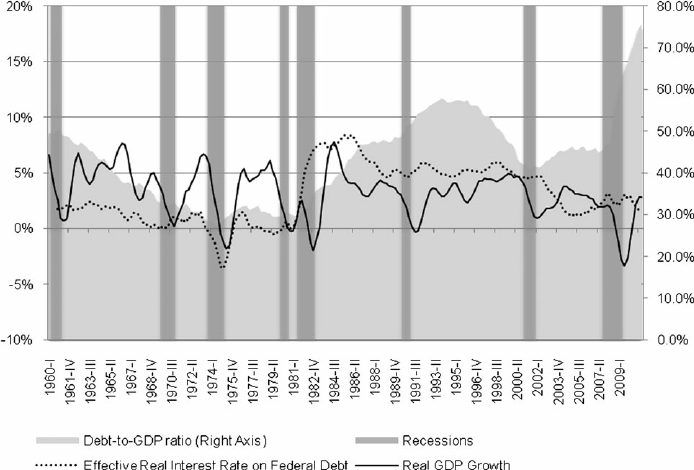

![]()

The interest rate has historically moved in line with the debt-to-GDP ratio until recently

Source: ResearchGate

The overall effect is that at debt capital will become more expensive and difficult to access. The immediate impact would be a decrease in demand for financial and real assets, leading to a drop in their prices. If this is mishandled, it can lead to a vicious cycle where:

- Asset price decreases, leading to a drop in valuation;

- Debt-to-equity ceiling becomes breached, leading to less credit being available;

- Investment falls and income (profit) drops;

- Business becomes less valuable due to lower profitability, leading to a further drop in valuation;

- When magnified across the entire economy, growth stalls.

b) Inequality and the rise of social-political instability lead to the rise of populism and eventually to a greater economic downfall

The rapid asset price appreciation as a result of central bank policies had the unintended consequence of exacerbating economic inequality across developed economies. Three pillars contributed equally to this:

- Increased asset price (induced by these policies) benefitted people with assets -> this meant the wealth gap between those with assets and those without were widened;

- Increased asset price also made assets less affordable, thereby decreasing the probability of people without assets of ever acquiring them -> people already with assets could acquire them and end up with more assets -> wealth gap further widened;

- Interest rate cut makes the cost of asset acquisition much lower than before. Borrowing at low rates became only accessible to people who already possessed assets.

So the poor become poorer, while the rich (who owned assets that went up) become richer.

“We have to be concerned about the wealth gap and the consequences geopolitically”, Ray Dalio

The link between rising inequality, growing social cohesion and by extension, political instability has been well-documented. Inequality fuels populism as we have seen with Brexit, the election of Trump, Salvini and the rise of AfD in Germany. Populist policies had historically been a headwind to long-term economic growth and therefore this decreases investors’ confidence in the future prospect of the global economy.